Babesia spp.

(Babesia spp.)

Babesia spp. are protozoans that infect wild and domestic cats worldwide. Babesia species that infect cats are not known to be zoonotic.

Distribution

Babesia infections in cats have mainly been reported from southern Africa but various species have a worldwide distribution[1].

Clinical signs

The main clinical sign is pallor (pale mucous membranes) caused by anaemia which is generally haemolytic and regenerative. Cats tolerate anaemic states better than dogs as they are less active; however, severe anaemia will result in weakness and lethargy. Icterus (jaundice), vomiting, diarrhoea and an unkempt coat are also reported. Cerebral babesiosis has been described in cats with B. legnau infection [2].

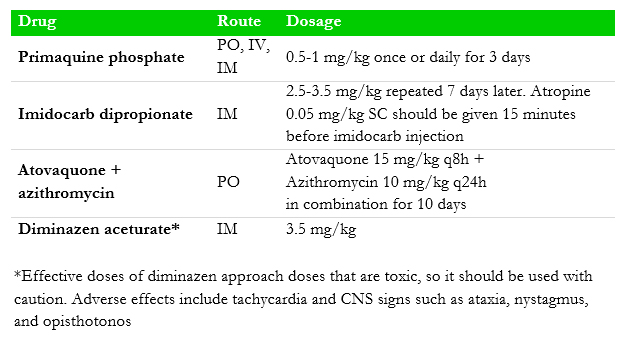

Figure 1. Babesia felis trophozoites (A, B) in a blood smear (Photo credit: Dr. P. Irwin

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of feline babesiosis is based on cytological examination of a stained-blood smear (Romanowsky-type stain) to identify characteristic red blood cell inclusions (Fig. 1). Babesia felis is a small piroplasm, very similar in appearance to B. gibsoni, but other species and larger forms of Babesia may be observed in some geographical localities. It is not possible to determine the species visually (although local knowledge is helpful). Reliable speciation of piroplasms requires molecular tools. The differential diagnoses for such inclusions are Cytauxzoon spp. and Theileria spp. (both piroplasms), and haemotropic Mycoplasma species. Serological and molecular diagnostic testing (PCR) are not widely available.

Treatment

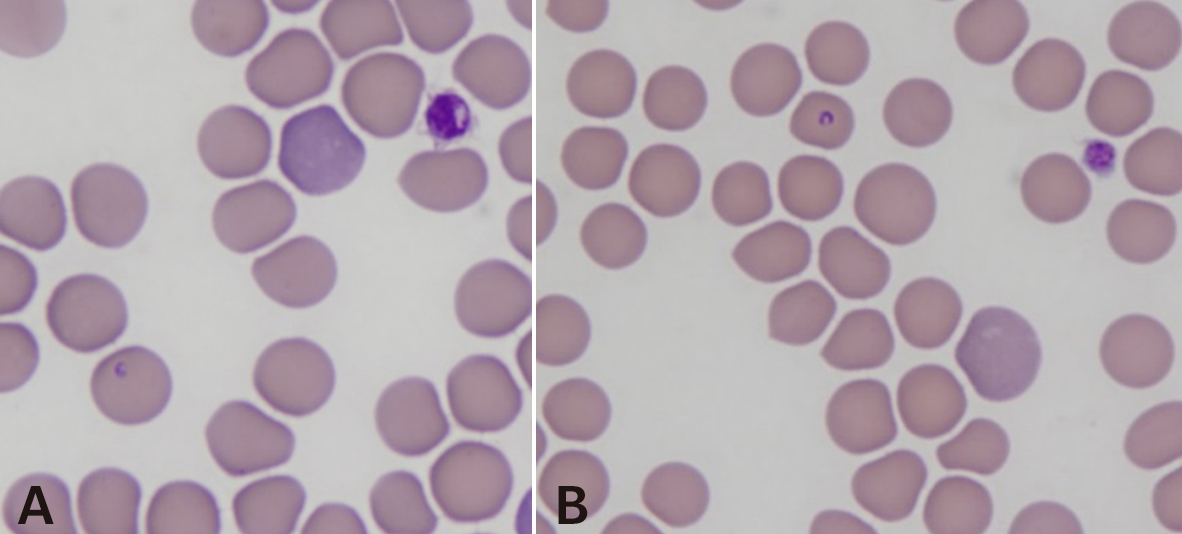

Most anti-babesial drugs that are commonly used in dogs have not been thoroughly tested for safety and efficacy in cats. Primaquine phosphate is used to treat B. felis infection, but the availability of primaquine is restricted to only a few countries. Given that the signs of feline Babesia infection are often relatively mild (and the efficacy and safety of most anti-babesial drugs unknown in cats) it may not be necessary to use an anti-babesial drug in some cases. If the cat is very anaemic, a blood transfusion may be required to permit clinical recovery and the development of stable (chronic) infection (be aware about the danger of incompatible transfusions in cats and always cross match or type the blood prior to transfusion). There are limited data for other anti-babesial therapy in cats and they should be used with caution.

Table 5. Routes of administration and dosage of commonly utilised anti-babesial drugs a in cats.

Prevention and Control

Prevention or reduction of exposure to tick vectors by utilisation of long-acting registered acaricidal products (topical solutions, collars) with repel and kill activity and keeping cats indoors to avoid fighting. Blood donors should be tested (by PCR) to rule out Babesia spp. infection.

Public health considerations

None.

References

[1] Hartmann K, Addie D, Belák S, Boucraut-Baralon C, Egberink H, Frymus T, Gruffydd-Jones T, Hosie MJ, Lloret A, Lutz H, Marsilio F, Möstl K, Pennisi MG, Radford AD, Thiry E, Truyen U, Horzinek MC. Babesiosis in cats: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J Feline Med Surg. 2013;15:643-646.

[2] Bosman AM, Oosthuizen MC, Venter EH, Steyl JC, Gous TA, Penzhorn BL. Babesia lengau associated with cerebral and haemolytic babesiosis in two domestic cats. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:128.